Getting solar PV and a battery seems like the logical response to reduce electricity bills and loosen the grip of the grid, and the retailers that have been profiting from your escalating energy bills.

However, let’s remove the emotion for a minute and take a close look at the economics of the decision whether or not to get a solar PV and battery system. The key mistake that many people make is to treat this as an all or nothingdecision. The nothing option is easy — resigned to the view that your electricity bills are all too boring and complex to do anything about, combined with the likelihood that you don’t know who to trust — you simply do nothing.

On the other hand the all option involves purchasing a large solar PV system and a battery to generate, store and use as much of your own electricity as possible. (For example, at today’s prices a 5kW solar PV system and a 12kWh battery might cost about $20,000 and a smaller 2.5kW solar PV system and 3kWh battery might cost about $10,000.)

You would think that an experienced installer or your electricity retailer would know what kind of savings these systems will generate but the reality is nobody can tell you with sufficient certainty. There are so many variables to take into account, including the crucial element of exactly how you as a consumer use electricity throughout the day and across the seasons.

Your retailer might have some insight into this if you have a digital interval meter, or smart meter, but they are not using this information to figure out what your savings could be. And considering that they make more money when you consume more from the grid they really have no incentive to help you cut your grid consumption.

The fact is that right now the typical payback period for energy storage can be as high as 30 years, and given that most decent battery systems come with a 10-year warranty, and power converters probably last about this long too, you’d be right to conclude that a payback period in excess of 10 years is a poor financial outcome.

The mistake though is to treat this as an all or nothing decision, instead of taking an incremental approach to the analysis.

There are some simple things that you can do today to cut your electricity bill, but beyond these simple, low investment options, you also need to decouple solar from storage because put simply, solar is relatively cheap and proven technology, whereas storage is expensive and nascent. There is no logical reason that you have to do the two together, and separating the two and running the numbers proves this.

Sellers of solar and storage equipment will typically look at your current bill and situation and compare this against the scenario where you install a solar PV system and possibly also a battery storage system that will store excess solar generation and supply this to your home during peak times.

To keep the economics simple we’ll just focus the simple payback period, that is, how many years it will take to pay back your investment. (Although this is not the most robust way to analyse investment decisions, it is the simplest metric to look at, and the one most commonly used to compare and express the economic benefits of these systems.)

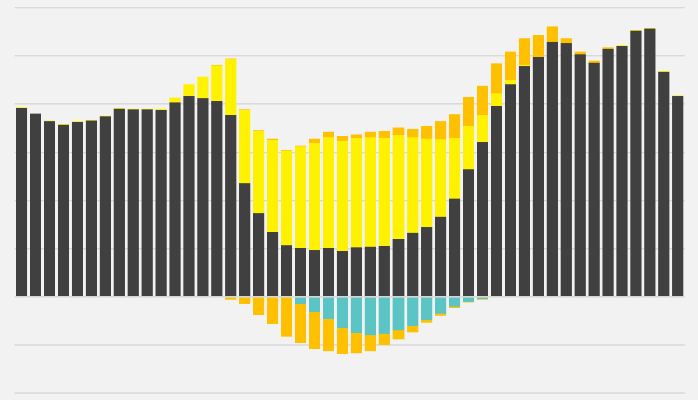

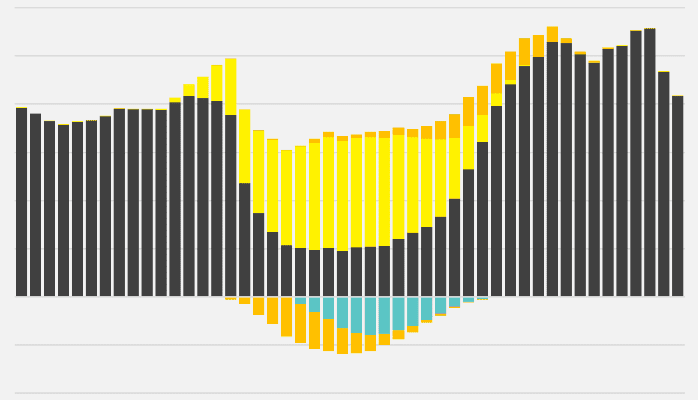

Absolute Approach

The “absolute approach” compares the result of doing something to the current state, that is, “buy system X or do nothing”. The table above shows that it seems to make good sense to get solar, as an investment of $4,000 provides savings of $600 each year, and you’ll make your money back in just under 7 years. Getting solar and storage together is not as good though, since an investment of $10,000 saves you $850 each year, and you only make your money back in 12 years.

Personally I feel like a 12-year payback period is a little too long, but I’ll leave it to you to decide whether you’d just go for solar or get solar and storage at the same time.

The problem though is that this analysis is fundamentally flawed for 2 key reasons.

The first issue is that adding a battery should be looked at incrementally. The battery adds $6,000 on top of the solar system and returns an additional $250 each year ($850 less $600), for a payback period of 25 years. Looked at in this way you would be right not to get the battery system. The mistake in the analysis above is that it looks at decisions in an all or nothing way, when in fact you need to look at each decision incrementally.

The second problem is that this analysis misses a key opportunity, and that is, you can easily, and generally for no upfront cost, save money by first switching to a better electricity tariff either from your current retailer or a new retailer * that offers a better tariff for your level of usage. For example, in New South Wales, the government website Energy Made Easy compares all available tariffs against one another and shows you how much you could save by switching. Switching generally costs nothing, and for our example household, can deliver large savings.

Incremental Approach

Adding in the option of switching tariffs and then taking an ‘incremental approach” to the analysis shows us that switching tariffs or retailer * can save $750 each year. After doing this, even getting solar looks like a borderline decision, and adding storage is definitely out of the question for now.

This appears to be bad news for solar and storage, but that is not the point. The point is what is good for consumers is to first take advantage of low cost and easy ways to save money on energy. The next step is to gather good data about how you use energy and work with someone you trust to give you the right advice, specific to your circumstances. The final step is to possibly invest in solar and storage technology to help you further reduce your bills and reliance on the grid.

For most people with average to high electricity bills, and good north or west facing roof space, solar will make sense today. However, storage is still too expensive for the mainstream consumer who wants to cut their energy bills. But all of this will change as battery costs continue to come down, the technology improves, additional revenue streams for the battery become apparent, and grid prices continue to rise.

Darren Miller is Co-Founder & CFO at Mojo Power.