Why is there such a big gap between people, industries and government agreeing we need urgent action on climate change, and actually starting? Scope 3 emissions are a great example. These are greenhouse gas emissions that organisations can influence, but don’t directly control.

Our research has identified the benefits of tackling these emissions in Australia’s urban water sector. If we consider the energy we use to heat water, water costs us far more than we think. It’s an issue of cost of living as well as water supply and energy infrastructure.

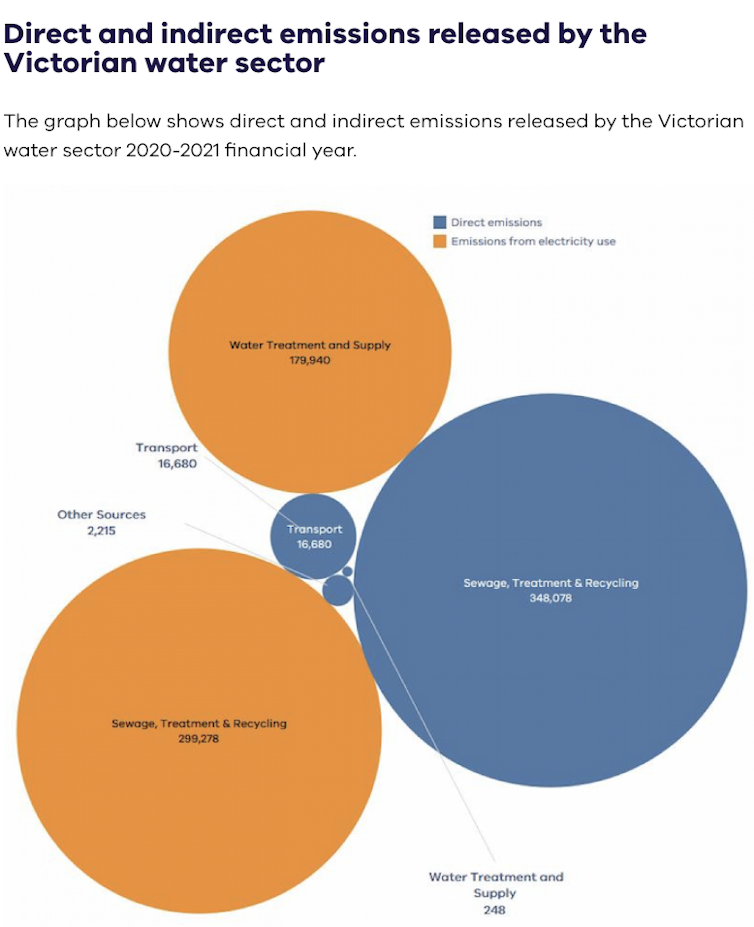

In Victoria, for example, water utilities are the largest source (about a quarter) of scope 1 and 2 emissions from the government sector. Scope 1 emissions come from activities utilities directly control, such as driving their vehicles. Scope 2 emissions are from the energy they buy.

Our research has found the gains from pursuing scope 3 emissions from the use of water that utilities supply could be about ten times bigger than their planned reductions in scope 1 and 2 emissions.

Extrapolating from Melbourne household data suggests domestic water heating accounts for 3.8% of each person’s share of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions – on a par with the 4.1% from aviation. Our research indicates that in Melbourne alone a city-wide program to retrofit showerheads could, by reducing water and energy use, have the same impact on emissions as taking tens of thousands of cars off the road.

Such a program would cost much less than all other renewable energy investments water utilities are making. It would also save water users money.

How to tackle scope 3 emissions

Water utilities don’t directly control scope 3 emissions, but they could influence what customers do. If they encourage more efficient water use, customers use less water and, in turn, less energy to heat it.

Water utilities account for 24% of scope 1 and 2 emissions from the Victorian government sector. While the sector has shown leadership in acting on these emissions, there is very little active accountability for, or even quantification of, scope 3 emissions.

Our research has found a Melbourne-wide program to retrofit showerheads to next-generation technology could save 12-27 billion litres (GL) of water a year (about 6% of current use).

The resulting energy savings would be 380-885GWh per year, cutting emissions by 98,000-226,000 tonnes. That equates to taking 21,000 to 49,000 cars off the roads.

Customers would also save up to $160 a year on their bills. The full economic benefit to society is more than five times the cost of the program.

Who influences water use? Everyone

Helping customers adopt highly efficient showerheads could cut emissions at much lower cost than all other renewable energy investments water utilities are making.

Most households don’t realise hot water systems account for around 24% of their total energy use. Their total energy use for water heating is larger as it includes appliances such as washing machines, dishwashers and kettles. An even larger percentage of household energy use is “water-related” if pool filtration, rainwater tank pumps and so on are included.

We think only of the savings on water bills, but efficient water use also affects our power bills and emissions. But communicating the link isn’t easy.

Showerhead manufacturers tell us they aren’t promoting efficient showerheads because they respond to demand. Water utilities don’t invest in them because it is a present cost for a future benefit – it doesn’t help them balance their budgets. And for policymakers it’s hard to celebrate the water and energy you don’t need to consume.

The combined impact is lack of action on saving water to reduce emissions – even though it’s a great option.

A ‘tragedy of the commons’ dilemma

Without direct control or accountability by any one organisation, we face a “tragedy of the commons” – individuals overconsuming a shared resource at the wider expense of society. The limited resource today is the ability of our planet to process greenhouse gas emissions before they change our climate.

The tragedy of the commons was used to describe externalities: costs borne by others that a decision-maker does not pay for. Examples include the future costs of increased flooding, more severe droughts and bushfires, and rising sea levels.

If we fully considered the costs and benefits to consumers and society (rather than just costs to utilities), investment priorities would change towards “least cost to the community” solutions.

Many water utilities will be carbon-neutral for scope 1 and 2 by 2025. This means they are at the global forefront of reducing emissions – but the water industry can do much more by tackling scope 3 emissions.

Committing to a scope 3 reduction challenges a water company to move toward things it can only influence rather than control. So, does it pursue all possibilities, without knowing if it can cut emissions? Or does it take a conservative approach and commit to only scope 1 and 2 emissions?

Reducing emissions from water use requires community, industry and government to act together. The stumbling block is decision-making and current legislation.

Simon Maddock/Shutterstock

So, what is the solution?

First, we need to call out the problem.

Second, we must find a way to ensure the reward for pursuing action is higher than the penalty for failure. A key to this will be highlighting how much cheaper and better many actions are that focus on scope 3 emissions, rather than solely “within business” strategies. We need to find solutions that are genuinely “least cost to community” rather than “least cost to individual business entities”.

Third, as a “commons”, this challenge must be communicated beyond utilities and government to communities. There needs to be broad understanding of the benefits of new approaches and of the pitfalls of a “do nothing” approach.

Big savings are up for grabs in the water industry. More broadly, all industries (from manufacturing to mining) need to consider scope 3 emissions from use of the products they sell.![]()

Steven Kenway, Research Group Leader, Water-Energy-Carbon, The University of Queensland; Liam Smith, Director, BehaviourWorks, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University; Paul Satur, Research Fellow for Water Sensitive Cities, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University, and Rob Skinner, Professorial Fellow, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.