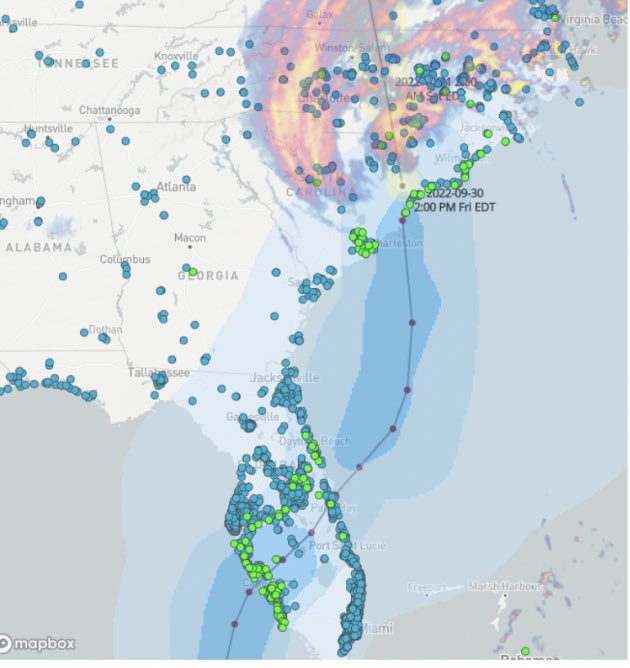

Microgrids created electric sanctuaries in Florida, Georgia, Virginia and the Carolinas after Hurricane Ian made landfall in southwest Florida in September, packing winds as high as 155 miles per hour. The storm knocked out power to more than 2 million people, leveled homes and sparked floods and water shortages while sending sharks swimming through streets.

Microgrids kept power flowing in at least three residential communities, plus retail establishments, medical facilities, a university and manufacturing operations in the four states.

With medical and emergency services needed in the wake of the hurricane’s destruction, a number of critical service operations gained power from microgrids.

A hospital in the storm’s path powered by a PowerSecure microgrid was one of the few hospitals in the area with a backup microgrid and clean drinking water, said Debra Phipps, director of monitoring, PowerSecure.

“For a time it was the only hospital in the immediate area able to take new patients and many patients were transported to this hospital from other locations to be cared for,” she said.

Microgrids for emergencies

Also working to supply electricity to meet the needs of those who provide critical care and emergency response services was FootPrint Project, a non-profit that provides clean energy systems such as microgrids during emergencies. It partnered with New Use Energy, Tesla, Sunrun, Schneider Electric and others.

Smart Aid International and Footprint Project are working to deploy a solar microgrid trailer in Lakeland, Florida, said Paul Shmotolokha, CEO of New Use Energy Solutions, which provided the solar microgrid. The trailer included 1.26 kW of lightweight solar panels, with the ability to expand the system an additional 1.5 kW. It’s especially suited to emergencies because it weighs a low 2,300 pounds and can be towed by a Subaru, he said.

Footprint Project also deployed microgrid systems to help power Toolbank USA’s disaster services trailer in Punta Gorda, Florida, according to a LinkedIn post from Footprint Project. In addition, Footprint Project set up a temporary solar microgrid for Charlotte County Fire emergency services in Florida, as well as for the Port Charlotte Christian Academy preschool. This afforded children, parents and child care providers light and a place to charge their phones, laptops and e-learning devices.

Vicki True, a spokeswoman for Schneider Electric, noted that Schneider has donated $50,000 as a leading supporter of Footprint Project, donating solar PV inverters for the organization’s solar trailer builds.

PowerSecure monitors over 1,000 microgrids in Florida

Over the past week, microgrid provider PowerSecure has kept an eye on more than 1,000 of its microgrid sites in the areas hit hard by the hurricane. The company managed nearly 700 individual power outage events, including 573 in Florida, 57 in South Carolina, 51 in North Carolina, nine in Virginia and six in Georgia, said PowerSecure’s Phipps.

The company monitored 1,093 microgrid sites that provide 750.4 MW of generation in Florida, 267 sites in North Carolina providing 210.2 MW, 86 sites in South Carolina that generate 106.7 MW, 87 sites in Virginia that yield 72.4 MW and 58 sites in Georgia that supply 58.8 MW, she said.

“The importance of energy and community resilience against natural disasters is top of mind and climate change is driving the need for an increased focus on resilience,” said Jared Leader, director of resilience for Smart Electric Power Alliance. He noted that as of noon Thursday, 1.86% of customers in Florida were still without power.

BlockEnergy keeps lights on in neighorhood

Meanwhile, at least three residential communities equipped with solar microgrids met the electrical needs of their residents during and after Hurricane Ian.

In Tampa, Florida, an Emera Technologies BlockEnergy microgrid platform owned and operated by Tampa Electric served the Southshore Bay residential development.

The community consists of 37 new homes that are all equipped with rooftop solar PV that produces electricity that’s shared in the neighborhood. Each home also has battery storage and a control system, said Rob Bennett, CEO of Emera BlockEnergy. The BlockBox controls connect to a neighborhood distribution network, he said. Also included in the pilot project are a central energy park with additional batteries and a connection to the power grid, he said.

Cherie Jacobs, spokesperson for Tampa Electric, said that the Southshore Bay area lost power during Hurricane Ian, but the microgrid system kept the 37 homes energized through the storm and the days after the hurricane hit.

The entire system can isolate from the main grid and every house can isolate from the neighborhood microgrid system, said Bennett.

This type of system is especially helpful in new communities, he said. The utility doesn’t have to upgrade its grid to meet the needs of new neighborhoods and the microgrid system can provide grid services.

“We can connect or interconnect to the main grid or separate any home,” said Bennett.

Under the model used in the community, homeowners pay for electricity at the same metered rate they would without the microgrid, and there are no extra grid charges or fees. Up to 80% of residents’ energy comes from solar. Because Tampa Electric owns and operates the microgrid system, residents didn’t have to hire contractors or deal with permitting and interconnection.

“Our home performed perfectly”

A second residential microgrid system that operated through the hurricane is Hunter’s Point, a new LEED Platinum and net-zero community in Cortez, Florida. The neighborhood is designed to withstand Category 5 hurricanes.

“During the most recent hurricane Ian, our home ran on the battery generated by the solar panels as the grid was down for days, and our home performed perfectly,” said Marshall Gobuty, founder and president of Pearl Homes, which developed Hunter’s Point.

The community is net-zero, which means that each home generates more power than it consumes. When completed, the community will include 86 single-family homes as well as 20 hotel room and condo units, plus some commercial space. No fossil fuel is used by the microgrid community. Residents are expected to pay only $40 a month–the minimum payment for being connected to the Florida Power & Light (FPL) system.

The Hunters Point homes operate from solar generated on site, but Florida law requires residents to connect to the local utility rather than operate off-grid, said Gobuty.

A third community served by a microgrid is Babcock Ranch, in Punta Gorda, Florida, which NPR and other news outlets reported as having operated through the hurricane, thanks to a microgrid system.

Babcock Ranch has an 870-acre solar farm operated by FPL that includes two 74.5 MW solar facilities, according to information from the utility.

The ranch was developed by Kitson & Partners.

EV acts as a home microgrid

In Florida, homeowners are beginning to recognize the need for resilience, whether in the form of an electric vehicle that can help charge a home, or a home microgrid.

For example, one Florida resident, Westley Aaron Ferguson, Orlando, tweeted that his Ford-150 Lightning helped power his refrigerator and other appliances during the hurricane.

And Oksana Fabri, a resident of Coral Springs, Florida, at the end of 2021 purchased from New Use Energy a folding solar panel and PowerPac battery and inverter capable of providing electricity to essential and some non-essential loads. While Fabri, who lives with her elderly mother, didn’t lose utility power during Hurricane Ian, she’s comforted by the fact that she has the microgrid.

“Having a backup plan gives the feeling of security,” she said.

This article was originally published by Microgrid Knowledge. Reproduced here with permission. To read the original version, click here