More and more of the world’s people are feeling the impacts of climate change. As United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said when COP27 opened this week: “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator.”

Much of the weight on the accelerator is coming from the construction and building sector. Accounting for 37% of global carbon dioxide emissions, the built environment is a major part of the climate change problem. That also means it can and must be a key part of the solution.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has just released its 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction at COP27. Its findings are alarming.

The sector’s energy consumption and emissions have rebounded from the COVID pandemic to an all-time high. Emissions are 2% higher than the previous peak in 2019.

The report says the reasons include revival of construction activity suppressed during lockdowns, and more intensive use of existing buildings.

In 2021, buildings accounted for more than 34% of the world’s total energy demand. This figure includes embodied energy that goes into construction materials and processes, and operational energy that goes into running buildings. The sector produced about 37% of CO₂ emissions.

The gap between the sector’s performance and what needs to be done to achieve decarbonisation by 2050 is widening – despite a 16% increase in investments in building energy efficiency from 2020 to 2021.

How do we measure progress?

The Paris Agreement seeks to avoid catastrophic climate change by limiting global warming to 1.5℃ and no more than 2℃. The Human Settlements Pathway of the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action identifies two objectives which are building momentum across the sector:

- by 2030, halve built environment emissions, with 100% of new buildings to be net-zero carbon in operation

- by 2050, all new and existing built assets must be net zero across their whole life cycle, including both embodied and operational emissions.

To track the decarbonisation progress, the Global Buildings Climate Tracker has mapped a direct reference path to a target of zero-carbon building stock in 2050. The tracker has seven components:

3 impact elements:

- CO₂ emissions

- energy intensity

- share of renewables in buildings’ energy use.

4 action elements:

- investing in energy efficiency

- green building certification

- nationally determined contributions to include building sector action

- building codes and regulations.

So why is the sector going backwards?

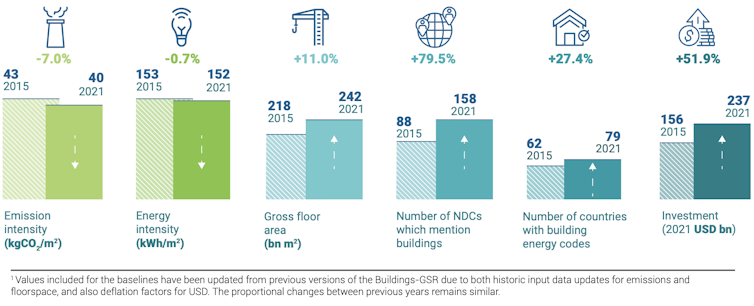

At first glance, the report offers some good news when comparing the 2021 trends to the 2015 baseline data. However, the overriding change is gross floor area, which has increased by 11% – 24 billion square metres – since 2015. This growth in construction, which is predicted to continue beyond 2050, is outweighing progress in other areas.

In addition, energy intensity has stagnated, falling by only 0.7%. Three-quarters of countries still do not have mandatory energy-efficiency standards for all building types. While an increasing number mention buildings in their nationally determined contributions, many still don’t have detailed plans for achieving net-zero emissions from the sector by 2050.

Global buildings and construction trends, 2015 and 2021

What does this mean for efforts to limit climate change?

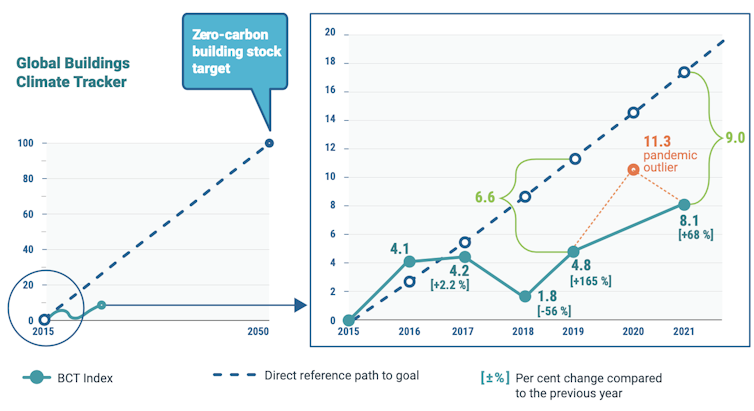

Overall, the report shows we have made less than half the progress we should have made on decarbonising the sector at this stage.

The gap has increased this year, meaning the situation is getting worse, not better. Urgent action is needed to get the sector back on track to zero net emissions by 2050.

Building sector performance compared to pathway to zero carbon by 2050

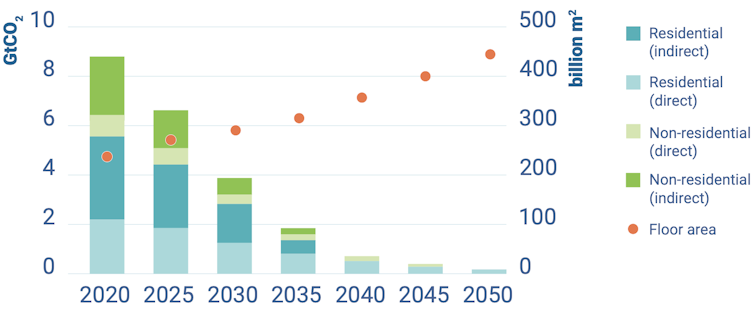

The report highlights the need to consider whole lifecycle approaches to emissions. That means taking into account emissions from the manufacture of materials and construction activity, through to the operation of buildings and then end-of-life demolition and waste.

For example, research in 2020 found total lifecycle emissions from the new homes required for Australia’s growing population greatly exceeded our emissions targets. Federal government projections potentially underestimated emissions by 96%.

What can be done to get emissions on track?

The report’s recommendations focus on strengthening:

- policies, targets and regulations

- investment and finance

- materials, with a focus on the construction supply chain, life cycle and circular economy.

Growth in energy demand and floor area under scenario of net zero by 2050

Priorities in Australia are to urgently update our building regulations; shift business models and investment to prioritise net-zero buildings and construction; and secure the electricity grid’s transition to renewable energy generation.

While the 2022 National Construction Code update increased energy-efficiency standards, further changes are needed to meet 2050 goals. Revisions to the code are notoriously slow, but the need for more action is urgent.

Australia is also yet to consider embodied carbon emissions in the construction, refurbishment and retrofitting of buildings, or the ongoing embodied emissions due to tenancy changes or home improvements.

We have seen improvements as a result of the Commercial Building Disclosure Program requiring commercial buildings to display their environmental rating under the NABERS standards. While no minimum requirements have yet been set, this program has helped to cut operational emissions.

However, unlike Europe, the NABERS rating generally only measures the base building operational emissions (as required under the Commercial Building Disclosure Program). It’s missing a big piece of the puzzle, tenancy emissions.

Despite the level of construction activity, most of the building stock has already been built and will not be replaced for decades. This means a retrofit program is needed.

It’s a huge challenge. For example, the City of Melbourne’s target of zero-carbon buildings by 2040 requires about 77 buildings to be retrofitted every year.

We have the know-how but need political will

We need political will and broadscale investment to bring about the scale of changes required to achieve net-zero buildings. Impetus is building, but it needs to translate into big structural changes in policy, finance, materials supply chains and energy systems.

The good news is we already have the capacity and know-how we need to steer our buildings sector onto a net-zero trajectory and off the highway to climate hell.![]()

Anna Hurlimann, Associate Professor in Urban Planning, The University of Melbourne; Georgia Warren-Myers, Associate Professor in Property, The University of Melbourne, and Judy Bush, Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.