If you search the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO)’s 2022 ‘Engineering Roadmap to 100% Renewables’ for the word ‘control’, it will naturally occur frequently. AEMO has control rooms, it is responsible for ‘system security’, that is, keeping the electricity system online in response to disturbances such as the increasingly frequent outages at coal-fired power stations.

Keeping the lights on is a serious responsibility. However, for every engineering problem, there are multiple solutions, and some are smarter than others.

Recently I recorded the history of AEMC’s responses to the need for technical standards governing distributed energy resources (DER). This article chronicles the history of AEMO’s approach to the rise of rooftop solar (in some quotations, emphasis has been added).

It’s a long history, which details the lack of transparency and accountability in AEMO’s approach to controlling rooftop solar, where it is acting as judge and jury and having state bodies act as executioner through blunt ‘solar cut-offs’.

It raises a lot of questions about decision-making on consumer-owned DER in the National Electricity Market (NEM).

In 2020:

On 30 April, AEMO published its Renewable Integration Study Stage 1. ‘Appendix A: High Penetrations of Distributed Solar PV’ stated that in 2020-21, AEMO would “collaborate with industry” to “mandate minimum device level requirements to enable generation shedding capabilities for new DPV [distributed photovoltaic] installations in South Australia (SA) (other NEM regions and Western Australia encouraged)”.

On 20 May, AEMO’s then-CEO Audrey Zibelman appeared on the 7.30 Report calling for new controls to enable AEMO to switch off rooftop solar in South Australia. She said: “This is very temporary, very limited and really… a last resort control we need if we were worried the system would otherwise go black.”

Following this unusual call for regulation, in late June the SA government released a ‘Consultation on the Proposed Remote Disconnection and Reconnection Requirements for Distributed Solar Generating Plants in South Australia’. Submissions were due less than two weeks later, on 10 July.

AEMO also published its ‘Minimum operational demand thresholds in South Australia ’ advice for the SA Government around this time.

It stated: “Demand recovery reserves will only be required when South Australia is operating as an island, when there are unusual power system outages or other abnormal conditions, or if unexpected major load reduction occurs. If the other mitigating actions recommended in this report are implemented, they should not need to be activated on a regular basis.”

This report defined two system security issues: rooftop solar disconnection on disturbance; and minimum load required to operate under islanded conditions, both of which are defined as risks if South Australia is islanded. Once the Energy Connect interconnector between SA and New South Wales (SA) is complete, this risk should fall to zero.

In addition, the report proposed that: “Trials should be conducted to verify real-time efficacy and coordination with the AEMO control room. Further investigation is required to determine the pathways for enabling this in real-time, and how this should be coordinated with NSPs. The most suitable regulatory frameworks for supporting rollout of this capability also need to be determined.” Such trials were never conducted, to the author’s knowledge.

On 28 September, the SA ‘Smarter Homes’ regulatory changes came into effect. These regulations require all new solar systems to have a ‘relevant agent’ with the ability to disconnect and reconnect the system when required by AEMO via SA Power Networks’ instruction.

This disconnection process means the household cannot consume its own solar generation behind-the-meter. The solar system is shut down, requiring consumers to purchase electricity from the grid uncompensated.

In 2021:

In January, the Energy Security Board (ESB) published its ‘Post-2025 Market Design Directions Paper’, which stated:

“The ESB intends to further consider the following options:

- Inclusion of ‘turn-up’ loads or load shifts in the Wholesale Demand Response Mechanism, which will allow customers without direct exposure to wholesale pricing to participate during low to negative price events.

- Establishment of an emergency reserve, similar to RERT, that incentivises off-market resources to become price responsive to negative prices.”

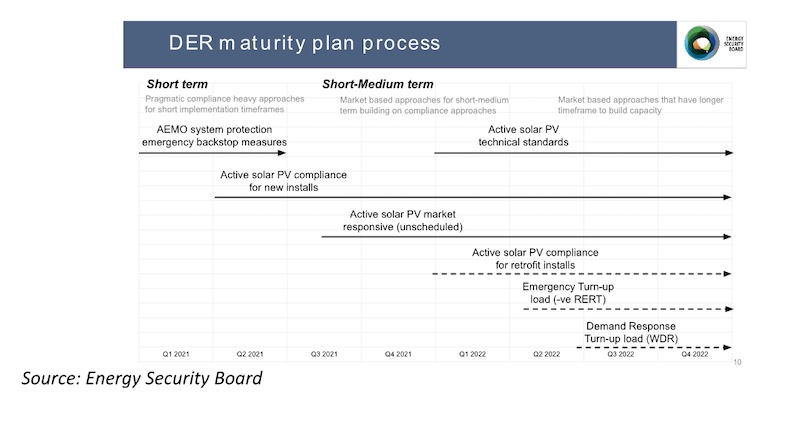

On 18 March 2021, the ESB presented a plan that included ‘Emergency Turn-up load (-ve RERT)’ in place by Q2 2022, and ‘Demand Response Turn-up load’ in place by Q3 2022 (see figure below).

On 14 March, on AEMO’s instructions, SA Power Networks coordinated the curtailment of 71 megawatts (MW) of rooftop solar:

- 14MW via ‘relevant agents’.

- 17MW directly through SCADA control of commercial and industrial rooftop solar.

- 40MW using ‘Enhanced Voltage Management (EVM)’, raising the voltage on the distribution network such that solar inverters trip off and disconnect (a crude and effective method).

It’s worth reflecting on SA Power Networks’ use of voltage raises for solar cut-offs. This requires the distribution business to elevate voltages to above the 253V, which is in breach of the distribution network service provider (DNSP)’s obligations, reduces the life of electrical devices, and in the worst-case scenario causes failure or fire. Yet this too has been implemented without transparency, cost-benefit analysis or compensation.

In April, IEEFA published Blunt Instrument: Uncompensated Solar Cut-Off Isn’t the Only Solution to the Minimum Demand ‘Problem’. The report included the following points:

- Neither the likelihood nor the magnitude of the PV disconnection risk when islanded, or of the minimum-demand risk, were calculated, just defined by AEMO as ‘rare’ or ‘very rare’.

- The definition of the problem was placed in question by the ‘solution’ in practice i.e. AEMO activated the solar cut-off during scheduled interconnector maintenance, not in an ‘emergency’.

- There was no development or evaluation of the most effective, least costly options for addressing the problem.

- There was no cost-benefit analysis of the proposed regulation, the SA Department of Energy and Mining stating : “Customer impacts were assessed as part of the decision-making process, with the benefits associated with these proposals considered to be greater than the costs”.

- These changes were outside NEM rulemaking and set a poor precedent for consultative, transparent and open policymaking.

The report highlighted that the advent of dynamic operating envelopes (DOEs) would be able both to address constraining solar within the bounds of the distribution network, and to enhance system security when required by AEMO.

This is a smarter solution with lower cost to consumers as it allows solar systems to continue to generate at a lower level of exports and/or simply enables self-consumption of the solar (at zero exports).

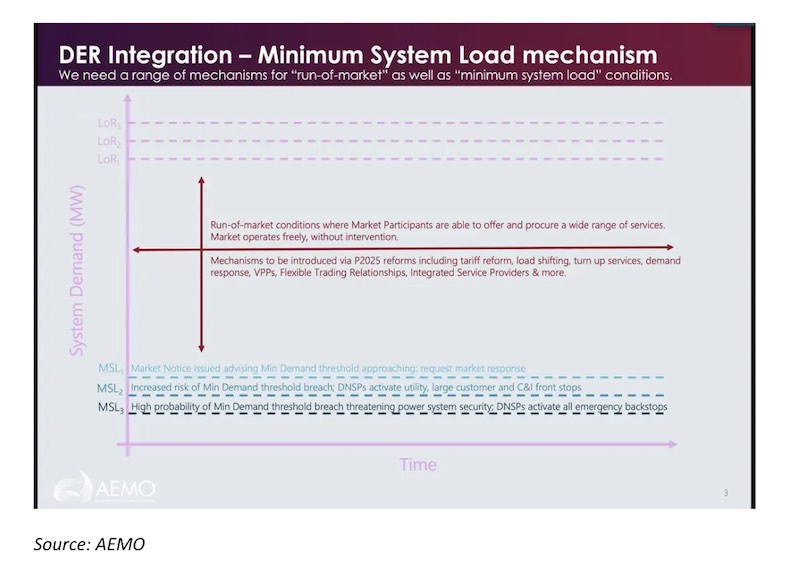

In June, AEMO’s then-general manager of new market services Scott Chapman said AEMO was considering a “minimum system load mechanism” equivalent to the Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader (RERT) peak demand mechanism (see figure below).

Chapman said this would “give transparency, and some order for everyone in the market to a) have input into how it’s designed, and b) have a level of transparency about what it is happening at any given moment”.

On 14 July, the new AEMO CEO Daniel Westerman reiterated this approach in his first public speech:

“It’s incumbent on all of us in the industry to improve how we engage, communicate and reward consumers. So I’m pleased to note that a collaborative effort is underway with rule makers, governments, industry and consumer groups to develop a tiered arrangement that would see rooftop solar constrained only as a last resort, and long after a range of steps with the ‘big-end-of-town’ had been taken to re-balance supply and demand.”

New market notices were subsequently created, but not the contracting or payments that exist with the equivalent RERT process. It is therefore unclear how market-based responses are revealed or ‘big-end-of-town’ steps are taken. There has been no “collaborative effort” on minimum demand.

In November, AEMO issued ‘Maintaining operational demand in South Australia on 14 March 2021’. The report included two positive updates: that AEMO had replaced its static minimum demand threshold with a dynamic demand threshold “which more accurately reflects forecast conditions when South Australia is at credible risk of separation”; and that SA Power Networks will first curtail DPV systems equal to and greater than 200 kW using SCADA control, before employing the smarter homes mechanism and EVM.

It also stated: “AEMO is, however, committed to providing greater transparency surrounding conditions involving the actual or potential curtailment of DPV.”

In 2022:

In September, Energy Queensland carried out industry consultation on solar cut-offs for Queensland. It featured no technical risk analysis, no detailed analysis of options or alternatives, and no detailed cost-benefit analysis. The consultation paper did set out example costs to consumers of solar cut-offs (at $10 for four hours), and the cost of the SA system blackout.

Energy Queensland stated its justification for introducing solar cut-offs is in “AEMO’s 2021 Electricity Statement of Opportunities (ESOO), which highlights declining demand and credible system security risks in Queensland, resulting from the ongoing connections of distributed energy generation without any capability to be managed”, but this does not supply the quantification of the likelihood or magnitude of risks.

However, the consultation paper did state: “An annual review of the emergency backstop mechanism will be undertaken to determine the ongoing need for the operation of the mechanism in light of emerging technology and options for customer participation.” In addition, the first DOEs had been applied in Queensland in the preceding year.

Energy Queensland’s requirements for rooftop solar exceeding 10kVA included the installation of a generation signalling device (GSD) or “ripple control”, which could be purchased from a local supplier for around $90. This is a very different method of controlling rooftop solar to SA’s controls.

The Clean Energy Council’s submission to the Energy Queensland consultation paper explained the issues with this approach: “Ripple control simply delivers an on/off switch and very little else… We urge Energy Queensland to move to use of 21st century interoperability technology instead of relying on the old ways of the mid-20th century.”

After considering the feedback, and nonetheless deciding to proceed with outdated ripple control devices, Energy Queensland applied the changes implementing solar cut-offs to its embedded generation connection standards, effective 6 February 2023.

From 12-19 November 2022, most of SA was islanded from the rest of NEM after storms blew over a transmission tower near Tailem Bend. AEMO issued instructions for solar cut-offs every day from 13-17 November and on 19 November for between four and 10 hours (up to a maximum curtailment of 400-600MW on 13 November).

Nexa Advisory has estimated the cost to consumers of this curtailment at $5 million.

Notably, AEMO has not published a cost to consumers of this solar curtailment. The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) and Australian Energy Regulator (AER) both have economic obligations to consider the cost to consumers of their decisions. It is not clear why the same requirement does not apply to AEMO.

In 2023:

In May, AEMO published its final report on the SA separation, ‘Trip of South East – Tailem Bend 275 kV lines on 12 November 2022’, which highlighted that for the 517 MW of rooftop solar capacity installed after the cut-off regulations, only 25%-42% were observed to respond as required in this event, while there was an 80% response of solar systems using DOEs.

The report details the advantages of DOEs, including that enrolled solar systems “have the capability for generator gross output to be limited to zero or to be disconnected from the network if export limiting is insufficient to meet curtailment requirements.”

Unexpectedly, AEMO then stated that DOEs for rooftop solar are “unlikely to be sufficient” to manage system security.

Victoria is also introducing solar cut-offs. From 25 October, an emergency backstop has applied to all new, upgrading and replacement solar systems greater than 200 kW.

In July 2024, Victoria will introduce an emergency backstop for new, upgrading and replacement rooftop solar systems less than or equal to 200 kW (small and medium-sized solar PV systems).

With interconnections to three other states, Victoria can never be islanded. It’s unclear from the information available how minimum demand risk applies in Victoria other than that AEMO has stated that minimum demand risk exists below 1.8GW (1,800MW) and that “Under these rare but plausible conditions, if is foreseeable that there could be no other way to operate the system securely except for reducing generation from DPV.”

The Victorian government has conducted modelling to estimate how often solar cut-offs might be needed. The modelling has not been publicly released, but according to its recent consultation paper, “emergency curtailment of rooftop solar via an emergency backstop mechanism may be needed for only 12-19 hours per year for the period between 2025-2027.

It is estimated that this will result in between $4 and $7 of lost feed in tariff payments per year for households with solar”.

Unfortunately, the technical analysis underlying this quantification of the cost is not available to energy market participants or consumers.

Also, as Evergen notes, this cost does not take into account the costs of compliance to original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), and ultimately to consumers; the implementation cost for distribution networks; nor the monitoring and enforcement costs to regulators.

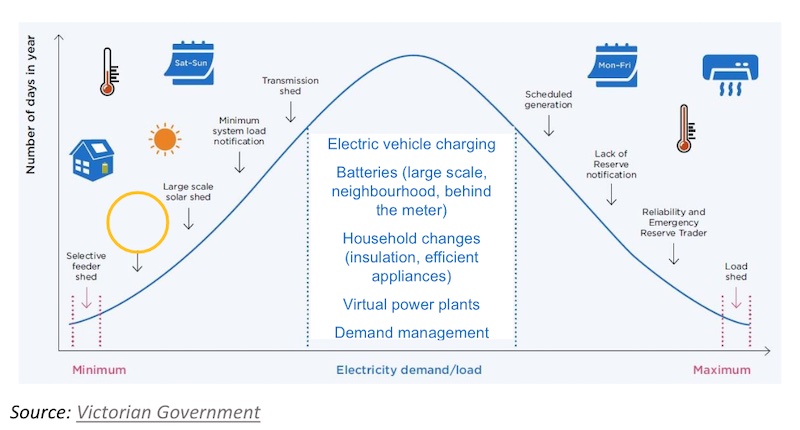

The Victorian government is undertaking a variety of other activities to assist with demand flexibility, as shown in the figure below:

In October, Westerman gave another speech stating the need for an emergency solar curtailment mechanism across the NEM.

Conclusion

What does this long history of solar cut-offs tell us?

AEMO is acting as judge and jury and having state governments and regulators act as executioner for rooftop solar.

The lack of transparency in its technical assessments is a concern. No probability has ever been quantified (we only have statements that occurrences will be ‘rare’ or ‘very rare’), and no magnitude ever quantified, so we have no transparent assessment of the risks in each state.

The only quantification is the minimum demand levels below which AEMO cannot manage the system securely, and AEMO’s assertion that it cannot manage the NEM without solar cut-offs. There may well be detailed technical risk assessments within AEMO, but they have not been publicly released.

Overall, there has been a lack of published scoping and analysis of options by AEMO and a lack of cost-benefit analysis at every stage.

Despite setting notification levels, AEMO has not pursued an “emergency reserve” contracting for turning up demand or turning down large-scale generation, as it does for the RERT and as promised in the ESB’s papers. If AEMO wants to incentivise Virtual Power Plants (VPPs), this could be one way to support their growth.

Disregarding any criticisms of the technical, economic and policy processes for solar cut-offs, some may say AEMO should have the ability to be judge and jury on behind-the-meter DER, owned and paid for by consumers. Except that is not the way the NEM has been established.

AEMO is the market operator and transmission planner, not the rule maker. It doesn’t get to decide which technical matters go into regulations, only into its guidelines, as specified under the NEM Rules.

This history suggests a rapid review of NEM governance arrangements is needed to support smarter DER integration and to ensure Australia reaches 82% renewables by 2030.

The body that is tasked with making National Electricity Rules is the AEMC. Should AEMO wish to have universal solar cut-offs across the NEM, it should lodge a rule change request with the AEMC, as it has done on other matters in the past.

AEMO’s state-by-state approach (some might say a “divide-and-conquer” model) leaves consumers worse off through greater complexity in DER connections and higher costs for OEMs and solar installers to adapt operations for each state.

Smarter solutions would include DOEs rolled out as a priority (this could be done through the rules if needed); and for governments to subsidise behind-the-meter batteries and support uptake of flexible demand, especially by mandating demand response capability of major household appliances. These measures were outlined in detail in the recent IEEFA report ‘Growing the Sharing Energy Economy’.

AEMO needs to step up its DER game and show consumers and industry that it not only has blunt control instruments at its disposal, but smart tools with benefits for consumers.

Dr Gabrielle Kuiper is an IEEFA Guest Contributor