Australia’s largest off-grid chicken farm – and one of the nation’s largest off-grid farms of any kind – has been completed in regional New South Wales and is being powered completely by on-site solar and battery storage.

The huge and innovative project – which sought Arena funding but did not get it – came about when Agright, a market-leading Australian and New Zealand poultry business, ran into trouble trying to connect its remote Meriki farm to the grid.

For starters, the property Agright wanted to farm, west of Griffith, was up to 19km away from the main grid connector, on a part of the network that was already pretty weak and verging on overloaded.

It soon became clear to Agright owner, Daniel Bryant, that it would be faster and cheaper to build a bespoke, stand-alone system to power Meriki’s operations, even with a combination of six staff houses, 40 large chicken barns and a bunch of water pumps and freezers.

“[Agright is] owned by one of Australia’s largest private equity funds and the [environmental, social, and governance] focus across all the portfolio businesses is quite intense,” Bryant says.

“We grow chickens for the leading processors in NZ and Australia under long term contracts and electricity and … gas are probably our largest input costs, alongside labour. So investing in solar quite heavily actually provides us with reasonable returns on top of ESG requirements.”

Bryant engaged Smart Commercial Solar to design and build a comprehensive bespoke energy system that would set a new benchmark for off-grid farms in Australia to meet both sustainability targets and financial goals.

“Given that it was going to take a couple of years to connect to the grid, we could build a solar and battery system quicker,” Smart CEO Huon Hoogesteger told an online briefing on the project on Monday.

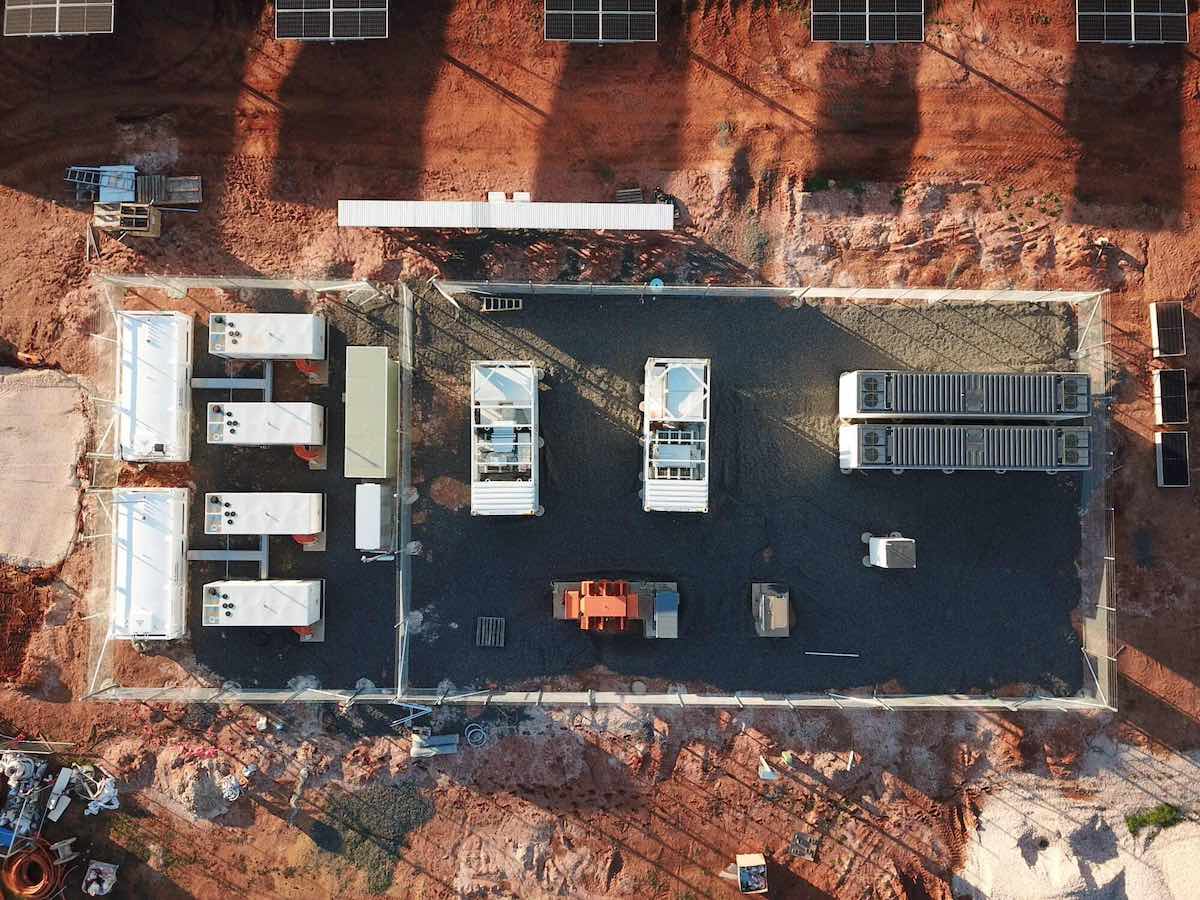

The result, now complete, combines a 3.98 MW ground-mounted solar system, a 3.4 MVA PV inverter, 4.4 MWh of battery storage, a 3.45 MVA battery inverter, an 11kV private distribution network covering 4.2km, a 2 MVA synchronous generator and six diesel generators for backup.

“This would have to be the most significant commercial solar and storage-driven off-grid project in Australia, if not the world,” Hoogesteger said.

“Not only is it a landmark in terms of its capability, but it also shows that operating in remote Australia is no longer a barrier for businesses.”

Hoogesteger says that, aside from a few weeks of “significant teething issues” with getting the system commissioned, the solar and battery system has produced all the chicken farm’s power with no need for backup diesel generation since coming online in March.

“In early 2023 we started modeling based on some other chicken farm… load profiles that we had collected over the years and I said to Daniel, ‘yeah, I think we could actually do this.’

“Daniel placed the order on, I think it was the 28th of June (2023)… and by March 2024 we were able to provide solar and battery power to the chicken farm.

“The [microgrid] is a really cool system,” he says. “I would say this is the largest [high voltage] off grid system with quite a diverse load and diverse system design as well.

“We’re [now] just trying to understand the load profile a bit better. But so far, the results good in that we haven’t had to pull on any [diesel] generators for power – the solar and battery system’s holding up really well – and we’re producing clean energy for the farm.”

If this sounds easy, it certainly hasn’t been – although Hoogesteger says his company called in some of its “favorite partners” to get the project over the line over a remarkably short period of time.

“We’re talking about a 4MW ground mounted [solar PV] tracking system, using a particular type of inverter from Sungrow … which also charges the battery,” he says.

“From this central location where the solar and battery system is we distribute that power through an 11 kV line in three directions or more [to the 40 sheds and six homes] and then some extended lines out to water pumps and freezers.

“The whole system is backed up by 2MW of synchronous generators and then the farms, themselves, also have another level of … further backup just in case anything could possibly go wrong,” Hoogesteger says.

“So Daniel’s, chickens are protected by about four layers of redundancy so that they’re never without power because chickens without power means dead chickens – it’s all about protecting the health and wellbeing of those chickens.”

But powering the Meriki farm using a stand-alone, renewables-based microgrid was not the only goal of the project. The design had to have an eye to the future, too.

“One of the purposes here was to build the off grid chicken farm to provide ideally cheaper power and to accelerate the ability to connect that to a grid if possible,” Hoogesteger says.

That’s because Agright is in the process of setting up another farm about 9km down the road. And the plan is to establish a grid connection so that the solar and battery system at Meriki can supply both farms, and also provide services to the grid.

Bryant says this would be done using a business-to-business sales agreement where the first farm would sell down power to the second – the design of which he says is currently underway in collaboration with network owner, Essential Energy.

“That means we don’t have to establish another large-scale solar and battery installation … we can use the same one to power the second farm .. so it’d be quite a good, added benefit to do that in the future. And that’s the plan,” he says.

“One of the things about building an off grid system is that you end up building more solar than you need,” Hoogesteger adds.

“In this particular case, the amount of solar that we could produce that is not used because the batteries are full, is about 50%.

“There’s plenty of sunny days where the… batteries are full by 10 o’clock in the morning and therefore the solar is ramped down and has nowhere to go.

“And so by grid connecting this, or even providing this power down to another farm, even if even if it were a private connection, we will be able to uses all of the solar’s potential.

“In addition to that, because the plan is to connect up and augment the line back to the zone substation for Essential Energy, Agright will be able to trade this renewable energy out into the market, both for[frequency control ancillary services] and spot market trades.

“So there is potential for a new revenue stream that wasn’t foreseen in the in the original modeling.”

In the future, Hoogesteger would welcome government support for complex and innovative projects like this, that provide major agricultural businesses with a sustainable and clean energy supply.

“One of the interesting things about this project is we actually applied to [the Australian Renewable Energy Agency] to see if we could get some support funding as a microgrid,” he said on Monday.

“We figured that this was as good a case as any for a microgrid, supporting not only the six homes but the farming, the water filtration, water pumping, freezers.

“It is, truly, a microgrid. But unfortunately we were unable to get that funding.”

Sophie is editor of One Step Off The Grid and editor of its sister site, Renew Economy. Sophie has been writing about clean energy for more than a decade.