Australians installed 57,000 batteries in 2023, a fifth more than they did in the previous year and there is no expectation of that run slowing down, according to new data.

But the reasons why households are rushing into the battery market today is less about being an early adopting technophile, and more due to rising anger with the way the bigger energy industry is treating small generators.

Those 57,000 new batteries (representing 656 MWh of capacity) bring the total number of installs between 2015 — the year when the numbers were high enough to rate a mention on a chart — and 2023 to 254,550 battery systems, according to consultancy SunWiz’s latest annual Australian Battery Market Report.

This year, SunWiz is forecasting 70,000 home batteries will be installed, representing 788 MWh of capacity.

The economic case for a battery is finally beginning to stack up as consumers are pinged with higher peak power prices and ever-falling feed-in tariffs for rooftop solar, and as the rising threat of weather-related blackouts make off-grid security more desirable, says SunWiz managing director Warwick Johnston.

“Home batteries are democratising energy storage in the same way that solar power democratised electricity production,” he says.

“To generate and store electricity, you no longer need a coal mine or hydropower dam in your backyard, you just need solar panels and a battery.

“Nor do you need an oil well or petrol station to power your car – a growing number of electric vehicle owners fuel their cars with solar energy, and are looking forward to the day their car can also help power their homes.”

Anecdotal evidence from installers shows the duelling issues of rising power prices with falling feed-in tariffs are creating a class of engaged – and very ticked off – customers who are keen to kick energy retailers where it hurts, by doing their best to exit the market entirely.

Smart Energy’s Joel Power said in January that their existing solar customers and new entrants are both clamouring for batteries because of the gulf in power pricing.

And in places such as NSW and ACT which will begin charging households for exporting excess solar power during the day, the pain of not having a battery will be even higher.

Yes to batteries, no thanks to VPPs

Australia’s $25 billion worth of distributed energy resources (DER) – including rooftop solar, battery storage and EVs – are still a mystery to the broader energy industry, which is struggling to figure out what to best do with them.

That, and consumer attitudes around being as disconnected to the grid as possible, are likely behind the very low interest in joining virtual power plants (VPP), which connect distributed energy resources (DER) such as batteries or solar panels into a network and give third parties control over them.

“Last year, we concluded 14 per cent of home batteries were connected to VPPs. This year we haven’t observed any noteworthy acceleration of VPP uptake,” the Sunwiz report says.

“VPPs on offer appear to be making it easier to exit the VPP… VPPs that are growing successfully tend to focus on assets broader than home energy storage.”

The report analyses data from the Queensland Household Energy Survey and found that 72 per cent of respondents weren’t keen on handing over control of their expensive home solar batteries in 2023.

Queensland is one state which has fumbled through figuring out how to deal with DER, requiring them to be fitted with an old-school “kill switch” that would allow networks to switch devices off at will when they needed to.

The state has also prevented EV owners from charging their cars from their household solar, and has finally ended up with a more nuanced system that will give consumers flexibility while retaining some visibility over the energy generation assets in the networks.

Households beat developers

Households have been such major backers of home batteries that over the last eight years, more capacity was installed in townhouses, bungalows and shacks around the country than grid storage was able to be connected, says the SunWiz report.

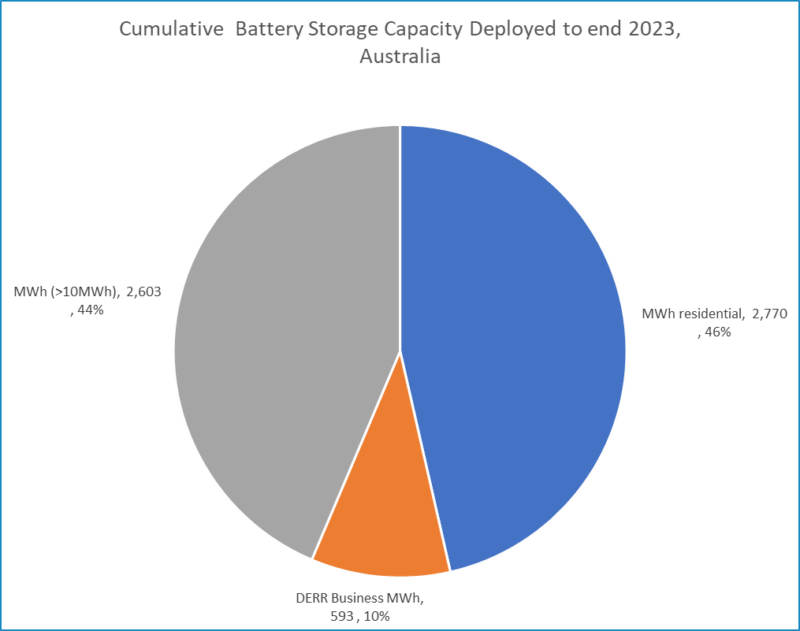

Those 254,550 battery systems installed since 2015 equate to 2,770 megawatt-hours (MWh), or the equivalent of the round-the-clock energy needs of 138,500 homes (if they all used an average 20 kWh of power a day).

The surprising fact that households are still beating big energy in terms of installed batteries, is because Australians fell in love with home storage well before commercial developers were able to figure out a large-scale business case, says Johnston.

“The people who buy batteries have generally been the innovators. Cost-benefit hasn’t been the driver for those people. On the flip side, state subsidies have incentivised customers,” Johnston told RenewEconomy.

“With grid scale, before Hornsdale [wind farm] these things were looked at as impossible. Then they were looked at as interesting but unicorns, and then they were looked at as things that make good sense but then the FCAS [frequency control ancillary services] market got cooked quickly.

“And now these things can do a whole lot of the grid and hence why they’re catching up fast.”

In the same eight year period, grid battery developers added 2,603 MWh of capacity to the national tally, but the balance between Australia’s small-scale early adopters and the energy gorillas is about to tip towards the latter.

Last year, a record 1,410 MWh of grid-scale batteries were installed.

“2023 was the year of the big battery, with deployment levels at twice their previous record. 2024 will be even bigger, with the capacity currently under construction at six times the amount at the same point last year,” Johnston says.