Over the past few decades, the booming global population, growing cities and changing climate have brought global attention to the need to build energy-efficient and sustainable buildings.

Evidence suggests that residential energy use increased during the pandemic. But what do we know about how people impact energy use in buildings they don’t occupy?

In a recent paper, our team at the Human-Building Interaction Lab uncovered that empty buildings consume more energy than we thought.

Buildings consume more energy when empty or partially occupied for extended periods because they are designed to depend on human interactions.

Empty buildings

Our research found that empty buildings consume more energy in colder climates because the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems need to compensate for lost heat usually generated by the daily activities of people in these buildings.

(Farzam Kharvari), Author provided

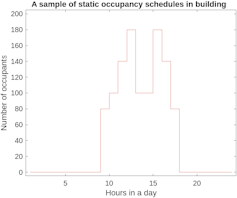

A primary reason behind the increase in energy use is static schedules that are used for designing buildings. Static schedules provide an hourly estimate of the number of people that would occupy these buildings. While these schedules are incorporated into the building design, they do not consider the actual number of people or their movements in buildings. As a consequence, our buildings were not able to adapt to emptiness during lockdowns.

Although the research on replacing static schedules with stochastic schedules — schedules that consider various factors and attributes including, but not limited to occupancy — is growing, our research demonstrated that implementing simple strategies like installing smart technologies can help empty buildings adapt to partial occupancy.

Using smart technologies

Technologies that sense the presence of people or count the number of occupants can help to mitigate the negative impacts of static schedules.

The simplest tech used widely in offices is occupancy sensors for lighting. A wide variety of products that control lighting in buildings, from simple auto-switches to smart dimmable lights, are easily available today. They primarily work with a simple indoor motion-detecting device that controls lighting and are capable of saving electricity efficiently.

Smart plugs can also reduce electricity consumption. Smart plugs allow you to control your devices remotely. But more importantly, they can be used to control the devices that use electricity when they are on standby and have the potential to reduce electricity usage for equipment.

Another tech used in buildings is demand-controlled ventilation (DCV), which helps to control the airflow and adjust the ventilation of the HVAC systems based on the occupancy. Research has shown that DCV is capable of saving energy significantly, especially in colder climates because the HVAC system needs to heat less outdoor air for the indoor spaces during partial occupancy.

It was also shown that reducing the thermostat setpoint in empty spaces significantly impacts energy savings in offices as the HVAC systems heat the space to a lower temperature. The arrival of smart thermostats can boost saving more energy in empty buildings. Having dedicated thermostats for different spaces within a building can not only result in saving energy, but also provide occupants with better thermal comfort.

Strategy is key

While using smart technology can help buildings adapt to partial occupancy, considering this partial occupancy during the design phase can maximise the building’s potential energy savings. For instance, offices with multiple floors or partitions can consider moving employees to one side or to one specific floor during partial occupancy.

Whether you are considering getting a new smart thermostat for your office or buying smart plugs, new tech can get expensive.

It is, therefore, important to start equipping buildings with solutions that encourage optimum energy and monetary savings. These potential savings can vary based on the climate, type of building and many other factors.

Individually assessing each building to gauge the performance of different technology and strategies can help sustain buildings in the absence of human interactions or partial occupancy periods. This in turn will help reduce emissions and strengthen our fights against climate change.![]()

Farzam Kharvari, PhD Candidate, Building Engineering, Carleton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.