Debra Phipps, of PowerSecure, had her eye on Hurricane Ida when it was little more than an oceanic disturbance. Years of experience, and her company’s state-of-the-art weather monitoring bureau, signaled to her that trouble was headed for the United States long before the rest of us were paying much attention.

The more she watched the progress of the disturbance — which would eventually grow into a dangerous Category 4 hurricane — the more worried she became. She sent out word to her team to make sure the microgrids in its path were ready.

Meanwhile, Will Heegaard, with the nonprofit Footprint Project, was also busy preparing in a different way. He and two other members of his team had decided to position three mobile microgrids in Tennessee long before Ida was a thought. They saw the state as a good staging point during the Southeast’s hurricane season.

But when Ida made landfall in Louisiana, Heegaard quickly realized the storm dwarfed what he had to offer. He sent out a plea to the microgrid community for help, and the community responded.

Same goal, different model

The work of PowerSecure and Footprint during Ida tell the story of the diligence, breadth of technology and range of response that the microgrid community now brings to disasters.

Their stories also showcase the diversity of the microgrid players involved. PowerSecure is one of the companies most active in the industry and a subsidiary of utility giant Southern Company. In contrast, Footprint Project is a small, donor-based rapid relief organization.

Both played a significant role in keeping the electricity flowing for those who were lucky enough to be within their reach after the storm pummeled the grid and 1.2 million people lost power, beginning in late August.

Here’s how the early days of Hurricane Ida played out for each.

PowerSecure and the hurricane oracle

PowerSecure constantly monitors more than 2,000 microgrids with 3,200 fossil fuel powered engines across a large swath of the US from its sophisticated network operations center in North Carolina.

“We not only provide microgrid support for hurricanes, but for all severe weather outbreaks like last year’s derecho, tornadoes, nor’easters, Arctic blasts, planned power outages and public safety power shutoff events for the western wildfires,” said Phipps, who is director of PowerControl Monitoring Operations at PowerSecure.

But it is the coast that gets special attention during hurricane season.

“There’s a lot of preparation on the front side, so we’re monitoring any wave or little cluster of thunderstorms during hurricane season,” said Phipps.

Phipps realized the gravity of what was coming a week before Ida landed on the Gulf Coast, even before it moved through the Caribbean.

“I’ve been doing this for 15 years. Some people call me the oracle. I kind of have a knack for knowing which ones are going to be strong and cause problems,” she told Microgrid Knowledge. “I said this is the one we need to prep for. Let’s start.”

A week before the storm made landfall in the US the company began doubling down on testing its microgrids — beyond their routine weekly check — to be sure they were all in good working order. The team checked diesel fuel levels and made sure no repair alarms were on, “even a little minor alarm,” Phipps said.

PowerSecure also notified service technicians to be ready to move in and repair any damage when the danger of the storm ebbed.

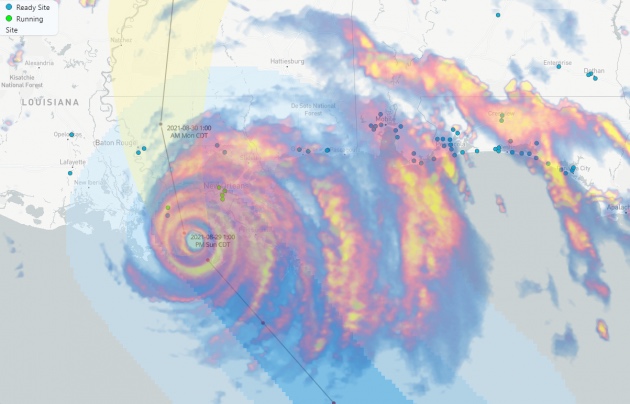

PowerSecure’s vigilance paid off. The map below shows its microgrids operating on Sept. 2, providing power to stores, a distribution center and a water municipality, a manufacturer, data centers and others.

At that point — three days into the storm — local utility, Entergy, had restored only 167,000 of the nearly 950,000 customers who had lost power.

PowerSecure had 38 microgrids in the storm’s path. They range in size but most are 1,250 kW and powered by diesel. Fifteen are permanent installations and the remainder are mobile microgrids.

Ida marked the second time in two years that PowerSecure was able to show the worth of its microgrids in Louisiana.

A year earlier its microgrids withstood a frontal attack from Hurricane Laura, another Category 4 storm. The brunt of the storm, the eye, made straight for microgrids that PowerSecure operates for two Rouses grocery stores.

“They [the microgrids] continued to operate after the backside of the eyewall went completely over them. And for three full weeks afterward, until utility power was restored,” Phipps said.

The stores were a “lifeline” for the community during the power outage, a place for people to procure much needed ice, water, food, medicine and baby formula. Line workers were able to get a hot meal.

We need power. Get here

It was a music festival that put the Footprint Project team in the right place at the right time to respond to Ida.

Footprint had been invited to power the Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival and build a mobile solar/storage microgrid at the event as a way to educate the expected 70,000 festival-goers about the technology.

Footprint’s participation in the festival was part of the organization’s strategy to make good use of its mobile microgrids when they are not needed for emergencies. Such events provide revenue to help fund Footprint’s emergency work.

Heegaard, Footprint’s operations director, saw Bonnaroo as an especially good opportunity because the festival was in Manchester, Tennessee, a good staging point to respond to hurricane disasters in the Southeast.

Little did he know that the festival would never happen. His microgrids were in place, but the event had to be canceled because of rain driven by Ida.

So Footprint’s plans quickly changed. Heegaard, a registered emergency medical technician who previously worked with the International Medical Corps deploying solar refrigeration in West Africa during the Ebola outbreak, found himself instead on the phone with disaster relief workers in Louisiana. The grid was failing and they needed Footprint’s help.

“We had multiple partners saying, yes, we need power. Get here. We have places you can drop your trailers. We have beds, floors, you can sleep on. Just get here as soon as you can,” he said.

As they waited for the storm to subside so they could enter Louisiana safely, the Footprint team began to prepare, stocking up on water, gasoline and other essentials so that they did not put pressure on what were likely to be scarce resources in the area.

As the hours wore on, Heegaard became increasingly worried — he only had a team of three (including himself) and three solar microgrids. Their capabilities were dwarfed by the need rescue workers were describing.

“Our trailers were stuck in the mud,” Heegaard said. “We had all of 50 battery packs, three solar trailers, a bunch of charging station gear that we were going to use for the festival, and a bunch of loose components.”

So Heegaard sent a plea to the microgrid community via email, social media and the press. The response, said Heegaard, was tremendous.

Even before Hurricane Ida, Footprint had begun to capture industry attention. In July, Schneider Electric became a strategic partner to support Footprint’s microgrid efforts. And utility giant Duke Energy has joined forces with Footprint to build a prototype mobile microgrid to learn how the technology works for use in outage restoration.

But Footprint’s efforts in Louisiana put the organization on the microgrid community’s map. More than 50 companies and organizations responded to the plea, netting more donations of equipment, expertise, volunteers and money from that one request than the organization had received in all of 2020.

“We had never had this much momentum behind a deployment,” Heegaard said.

SkyCharger, which specializes in low-cost charging, sent trailers that were refurbished by microgrid monitoring and control company New Sun Road.

Equipment and expertise also came from microgrid giants Tesla, Schneider and PosiGen, a solar installer founded after Hurricane Katrina that focuses on low-income households.

The DER Task Force, an online energy community, launched a fundraising campaign that brought in $60,000 from individual donors. The task force’s campaign has since evolved. Spring Lane Capital has joined to help Footprint pursue institutional and corporate donors for its climate disaster response efforts nationwide.

As a result of the support, Footprint was able to bring microgrid power to 20 relief sites in Louisiana, many of them at churches or community centers in areas where the storm had landed its hardest punch.

The sites distributed food, water, medical supplies and other essentials, while providing Wi-Fi for those shut out from communications.

The microgrids powered refrigerators and freezers for a community kitchen in Houma and a church in Bourg where people could process FEMA paperwork.

They served a tribal center distribution site in Pointe-au-Chien, as well as families and low income neighborhoods, camps where volunteers slept, and others in need of power.

The teams focused much of their effort south of New Orleans in communities that were “just devastated completely,” Heegaard said. “Their houses are gone, just gone. Even when the grid comes back, there’s nothing to connect the grid to.”

Footprint has kept equipment in place to help serve some of those areas.

Not enough microgrids

PowerSecure and Footprint weren’t alone in bringing microgrid relief to Louisiana. Others were in the area as well. For example, Sesame Solar, in collaboration with Alpha Technologies and EnerSys, provided Comcast with mobile, solar-powered nanogrids to help with communications.

But the devastation wrought by Hurricane Ida — one of the costliest hurricanes on record — made clear that microgrids remain far too scarce in disaster prone Louisiana.

A month and a half after Ida, Entergy still has a list of communities on its site that lack power. One community isn’t scheduled to regain power until the end of 2021.

“We do need microgrids. It’s proven time after time,” said PowerSecure’s Phipps.

This story was originally posted on Microgrid Knowledge. Reproduced with permission.