In 2002 Rob Bruer landed a job monitoring the energy use of 10 Queensland schools that were donated solar panels by Stanwell Power.

The solar systems were tiny – just one kilowatt. This was back in the day when there were no government subsidies to install solar and “50 grand bought you a kilowatt,” Rob Bruer told the SwitchedOn podcast.

“I was just astounded by the use of energy within the schools.”

“Every ounce of the energy that those systems produced we consumed with a computer trying to capture the data back in the classroom,” Bruer says.

Although the project was “a bit of a joke really,” it got Bruer and his colleague Mark Stenhouse thinking about the way energy is used in schools.

“I just looked at it and went, we’ve got all this data about energy, but we’re not educating the people who use the energy.”

“We’re not putting that data and that power back into the hands of kids at school to actually create change.”

It was the beginning of Solar Schools.

With around nine and a half thousand schools in Australia, Bruer calls schools an “unforgotten resource.”

“Schools are a huge emitter of carbon because, on any given school day, a quarter of the population is at school.”

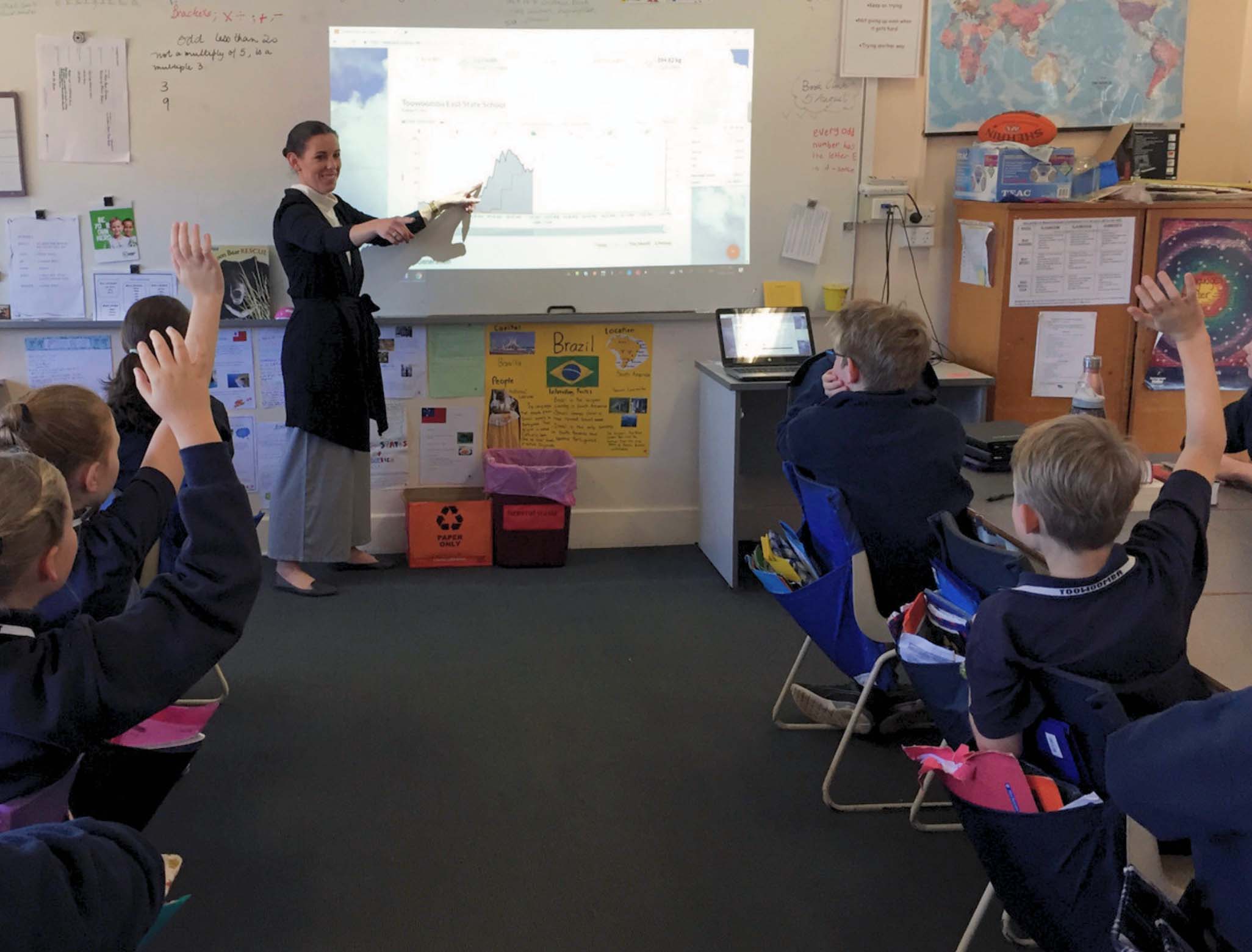

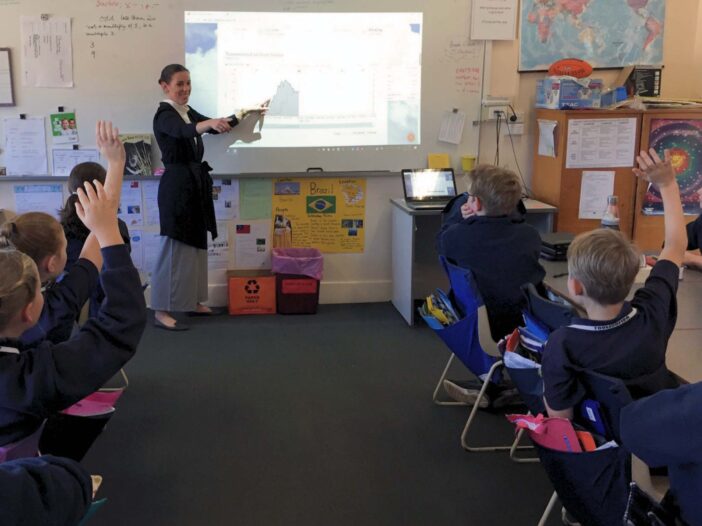

Bruer says the aim of Solar Schools is to create greater energy literacy among children so they can be involved in the decisions their school makes about where their energy comes from, and how that energy is used. For instance, what temperature the air conditioning or heating should be set at.

Greater energy literacy will enable children to have “an impact and be inspired to create change for the world.”

Solar Schools helped one school identify all the devices in the school that use standby power, which led each classroom to identify a representative who would turn off all the devices at the end of the day. The initiative saves the school $2000 a month on its power bill.

As a result of data collected by a South Australian school, the students voted to adjust the school’s heating thermostat during winter.

“Instead of trying to heat the classroom to 26 degrees, they set the thermostat down to 21 after experimenting with their energy and seeing what the difference is over a period of time.”

In 2023, the 600 schools Solar Schools worked with generated 62 gigawatt hours of solar energy. They used 44 gigawatt hours of that and 17 gigawatt hours was exported to the network.

That 62 gigawatt hours basically avoided the emissions of 45,000 tons of CO2 and saved taxpayers about $7.8 million.

Bruer argues that Solar Schools is “in some regards, incredibly successful”, but acknowledges “in some regards, really disappointing.”

Whilst Solar Schools helped the 600 schools save on emissions and dollars, the same schools consumed 105 gigawatt hours of energy from the grid at a cost of $16 million.

That’s because schools are consuming energy at an ever-increasing rate.

“In 22 years of monitoring energy in schools, I have never seen energy consumption decrease. It’s increased on average eight and a half to nine per cent a year.”

“On a bad year, it’s increased by 23%.”

Bruer attributes this increase in energy consumption down to the increased use of technology in our schools. From laptops and tablets, digital white boards, learning management systems like Google classroom, virtual and augmented reality, 3D printers, robotics kits, to various cloud computing systems, schools are guzzling power.

A major problem for public schools that want to better manage their energy use is their energy contracts are negotiated at government level, not by individual schools.

“If you’re not paying your power bill, you don’t really care about it.”

Bruer says some private schools think they’ll attract more students by building “a good-looking campus and putting fresh boats in the rowing shed,” rather than worrying about where their energy comes from.

Solar Schools also has to rely on teachers to convey energy information to their students, and they’ve found many teachers have a low understanding of energy.

Just making sense of a school’s power bill is beyond most teachers. “You basically need a PhD to read [commercial power bills],” Bruer says.

“It’s got all these weird and wonderful things that come out of the energy market on it, and the teachers don’t understand any of those things.”

Solar Schools is keen to get more solar onto school roofs, but admits many schools are a “tricky market” for solar.

A group of 25 private schools in north Queensland has managed to earn “a significant amount of money” by installing solar and batteries, and partnering with a local distributor to provide ancillary services for the network and grid stability.

However, government schools in Queensland “don’t get feed-in tariffs at all so there’s basically zero value [for a school] in that.”

For these schools there are large periods on the weekend and during school holidays where the energy they produce can’t be utilised by the school.

Bruer would like governments to recognise how significant schools could be for the energy transition, by rolling out solar and batteries “in every school in the country and have it core to the curricula and core to the energy mix in the country.”

You can hear the full interview with Rob Bruer on the SwitchedOn podcast.

Anne Delaney is the host of the SwitchedOn podcast and our Electrification Editor, She has had a successful career in journalism (the ABC and SBS), as a documentary film maker, and as an artist and sculptor.