To add battery storage, or not to add battery storage ….

That is the question many solar households in Australia are already asking themselves, as the winding back of solar feed-in tariffs coincides with falling battery costs and an influx of plug and play battery storage offerings to the Australian market. Not to mention soaring network costs.

Report after analyst report predicts that the battery storage market will take off in Australia over the next couple of years, led by a boom in the residential sector.

While there is an undeniable surge in interest in battery storage, the simple fact is that for most Australian households battery storage is not yet a value proposition. It may be that economics will not be the driving factor in the speed of uptake, but for many it will be.

That fact that was stressed again on Monday in a comprehensive report, released by the Alternative Technology Association, which aims to predict when, where and and for which sort of households, battery storage will stack up first.

“There’s a lot of hype in the community about battery storage, and while we think it is a great thing, we urge people to understand their own electricity consumption patterns and choose the most suitably sized and designed solar and battery systems,” said ATA policy and research manager Damian Moyse.

To do this, ATA researchers used a purpose built solar-with-battery economic feasibility tool called the Sunulator – which was launched in Melbourne on Tuesday – to analyse electricity data from 10 different locations (capital cities plus Cairns and Alice Springs), consumption data for typical working couples and young families, three different grid tariff types and different sized solar systems.

The results were mixed. For most households in Australia, the ATA found that battery storage would not make sense economically until 2020; but for some households in Sydney or Adelaide, it could be as early as 2018. It’s all about weighing up a number of key metrics –not least of all, the sort of tariff you are on.

“At today’s prices, most Australian households won’t be able to achieve a 10-year return on their investment – which is the typical lifetime of a well-designed and operated battery system,” said Moyse. “But by 2020, this will change for an increasing number of homes.”

This is illustrated in the graphs below, taken from the report:

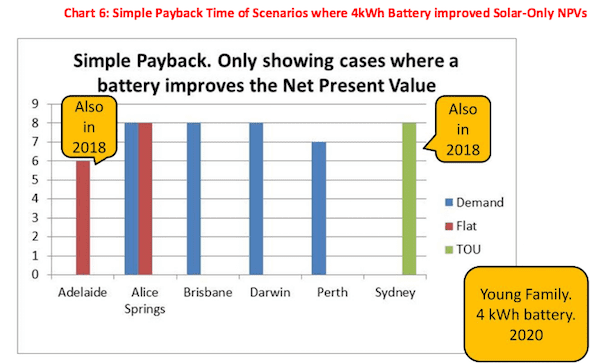

In nine scenarios across six locations, the report found that a 4kWh battery improved the net present value (NPV) for a “Young Family” across a variety of tariffs. As you can see below, households from only two locations – Sydney and Adelaide – achieved this with investment in 2018. The remainder involved investment in 2020.

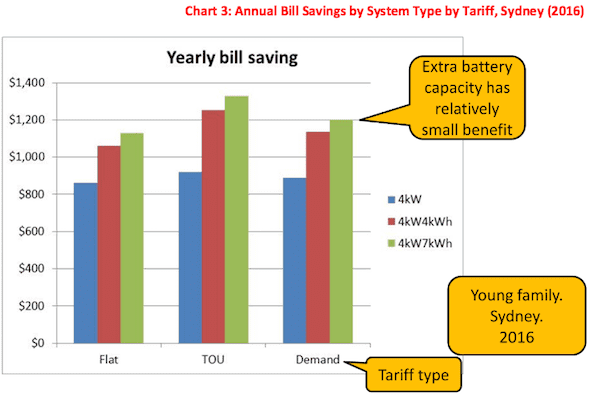

“Adding batteries did generally deliver savings over the ‘solar-only’ systems,” the report found – with annual savings

ranging from $132-$335 for a small battery and $187-$513 for a larger battery, dependent upon household type, location and grid tariff.

The study also found that the smaller 4kWh battery was always more attractive than the larger 7kWh one; and in no case did adding batteries significantly speed up the solar system payback time.

Of course, the report found that “smarter” battery systems – which could work with a given household’s time-of-use tariff to maximise both cheap energy storage and solar self generation – would deliver greater savings, especially if they incorporated weather forecasts.

“It remains to be seen when batteries this smart become available in Australia,” the report said.

The report also found that the economics of investing in storage would obviously be improved if households were paid to provide and share in associated benefits to the electricity grid.

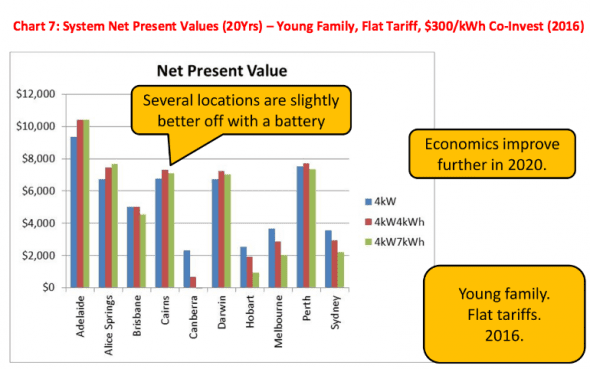

The chart below analyses a scenario where an energy company co-invested $300 per kWh, off-setting the solar

household’s upfront costs.

ATA suggests energy companies could co-invest in such systems, for example, by selling batteries cheaply to households and, on critical days, could control the batteries remotely, discharging them at peak times.

Likewise, though, it remains to be seen when energy companies this smart will become available in Australia.

Until that time, or until batteries drop further in price, the ATA suggests households try cutting their bills through more effective investments, including LED lights; gap sealing, insulation and window shading; efficient appliances; ditching the gas network; and solar without batteries.

Here’s their data on the current payback period of solar only systems for both household types.

And here’s another chart showing the additional bill savings ($, annual) from adding a battery to the 4kW solar system in each location. These are above that which would be achieved by the 4kW solar already:

And here’s another chart showing the additional bill savings ($, annual) from adding a battery to the 4kW solar system in each location. These are above that which would be achieved by the 4kW solar already:

Finally, the report calls on Australian consumers to get to know their own energy profiles and to embrace energy efficiency. And if they want to invest in a solar-battery system, perhaps test the economic feasibility first using the ATA’s Sunulator tool.

“Different consumption levels and different lifestyles require different solutions – no one size fits all,” said Moyse.

“Having a more energy-efficient home will mean you need smaller sized batteries, which will ultimately be better for your overall energy costs and the environment,” he said.

“Batteries need to be considered in the context of an overarching, holistic energy management approach – whether that be for a household or business.”

Sophie is editor of One Step Off The Grid and deputy editor of its sister site, Renew Economy. Sophie has been writing about clean energy for more than a decade.