At the moment it is de rigeur to try to seal off every last little crack in the envelope of one’s house in order to save energy. The message seems to be – if you don’t draught proof your house you can’t be serious about managing your carbon footprint.

This is fine as it goes, but there is another side to this issue: you also have to breathe! Almost every day I seem to come across calls in the energy media for everyone to seal their houses, but rarely do these pleas mention the need to maintain adequate airflows.

About two years ago, I began to be swept up in this trend. I did some very basic gap sealing around doors and closed off some unused vents in our house. I planned to progressively seal up the house once I had settled on our heating and cooling regimes. However, earlier this year I started to come across articles about monitoring indoor CO2 levels as a way to track indoor air quality. I became intrigued and decided not to do any further draught proofing until I’d carried out my own monitoring.

Why should we be interested in indoor CO2 levels?

A quick Google will reveal that high CO2 levels can be hazardous (and ultimately lethal) – see this US Bureau of Land Management paper for example. At high concentrations CO2 is both toxic and an asphyxiant (ie it will displace oxygen in the air) but there seems to some expert debate about the relative importance of these two effects. More importantly for this paper, research shows that for humans, task performance begins to degrade when CO2 levels reach about 1,000ppm.

The literature suggests you are not likely to find toxic levels of CO2 in your house unless you live near an erupting volcano or near certain mining/gas operations. By the same token, my monitoring suggests that even in a ‘normal home’ you may well have indoor CO2 levels that are high enough to affect your judgement and make you drowsy.

CO2 is important in the context of indoor air quality, since it is commonly the only indoor air pollutant that is continuously being emitted by the occupants of a room (via breathing). In an occupied room, if the ventilation is inadequate the CO2 levels build up until some, or all, of the occupants leave or fresh air is introduced (eg by opening a window or turning on an extractor fan).

Monitoring CO2 levels in our house

I bought a CO2 monitor on Ebay – this is shown in Figure 1. It is certainly not a laboratory grade piece of equipment but it seems fine for my purposes. When I began monitoring I was very surprised by the results.

I had imagined that our crudely draught proofed house would have good air quality given how many paths there are for air to enter and leave. In particular, at this time of the year, when we open our windows, I had thought that our CO2 levels wouldn’t be too far above the outside levels. I was wrong! Figure 2 shows a plot of one night’s CO2 datalogging in our main bedroom with windows open – the CO2 levels gradually built up over the night and, for a time, the levels exceeded the recommended acceptable level of 1,000ppm.

While I have only been monitoring for a week or so I am confident the data in Figure 2 is not an anomaly – it appears to be the norm. I am now quite fearful about what the levels will be in winter if we follow our usual practice and close all windows.

Responding to the high CO2 levels

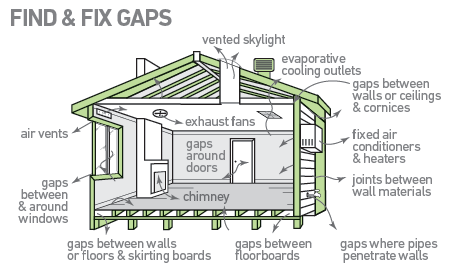

My initial reaction to my monitoring results has been to start undoing our draught proofing. I have unblocked some of the vents in our house and will progressively open up the house to see if we can keep our CO2 levels consistently below 1,000ppm throughout the year. In the end, if this is not achievable we may have to install a mechanical ventilation system.

To some, un-draught proofing a house will undoubtedly be seen as the wrong response. Indeed, if you have a house that is heated by some form of ‘warm air’ heating opening up air gaps could have a significant detrimental impact on energy use. However, this is not such a problem for us as we are heating our house with Far Infrared (FIR) panels. FIR heats people and objects, not air, and therefore our prime heating effect comes from direct radiant heat and not from secondary heat contained in warm air. Given this, I don’t expect our energy use will be significantly affected if we open up air gaps.

Recommendations and further reading

Don’t make my mistake. Don’t assume that just because you have a leaky house you have good indoor air quality. If you are planning to draught proof your house I would strongly recommend that you monitor your indoor air quality and work out how you are going to ensure good airflows.

I have prepared a more detailed paper on my CO2 monitoring which the reader may find useful.