The concept of energy resilience has come into sharp focus over the past few years in Australia, as devastating floods, followed by catastrophic bushfires, followed by more devastating floods have left some regional communities powerless – literally and figuratively.

A Royal Commission into the 2019/20 Black Summer of bushfires found that more than 280,000 customers from various energy providers experienced a bushfire-related power outage at some point, mostly due to fire damaged poles and wires. Some were without power for up to 10 days.

In response to this issue, networks, regulators and governments are (slowly and haphazardly) looking into how they can improve the electricity system’s preparedness for, and response to, power outages from storms and other extreme weather events.

At the network level, many of the answers to increasing resilience lie in the development of more localised energy resources like solar and storage-based stand-alone power systems (SAPS), community batteries and microgrids.

But that will take some time. So what can households, small businesses and communities do to improve their own energy resilience, in the context of more frequent, intense, prolonged and destructive weather events?

Total Environment Centre put this very question to Dr Glenn Platt, former head of the CSIRO Energy Centre, and backed by funding from Energy Consumers Australia commissioned him to research the subject.

The resulting 30-page report on autonomous energy resilience was published by the TEC this week.

“This year’s multiple catastrophic east coast floods reinforced what we learned in the bushfires of 2019-20,” says Mark Byrne, TEC’s Energy Market Advocate.

“When all hell breaks loose, we can’t always wait for the ‘cavalry’ – emergency services – to save us straight away.”

Platt’s detailed research finds that the options available to consumers to boost their energy resilience are diverse and variable, depending on the circumstances and energy loads of individual households. The report even has a section on “novel approaches, not commercially available.”

But Platt also distills down a list of seven key recommendations that can be made to most consumers, that could make a significant difference in reducing the risks they face during an electricity grid outage. We share them here:

1. Use a plug-in energy meter, or look at the energy efficiency label of appliances, to understand how much energy your appliances need, and decide which ones will be the most important to keep operating during a long blackout.

The report goes into some detail on this tip, and notes that the range of potentially critical appliances is quite broad.

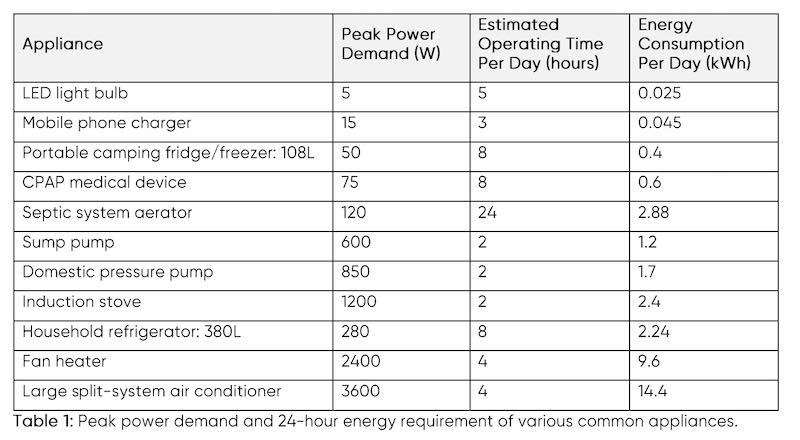

Essentially, when weighing the energy requirements of an appliance there are two key characteristics that need to be understood: Its peak (maximum) power demand at any one time; and total energy required over a certain period – say, 24 hours.

Platt supplies a handy reference table (below) with some examples of these.

2. Buy a windup or solar powered combined torch, radio and battery, so you can stay in touch with the outside world (including charging your mobile phone).

Source: Total Environment Centre

3. Have a backup source of electricity (such as a portable power station) ready, or some alternative appliances that don’t need grid electricity to operate (eg solar hot water systems and cookers).

The report provides various examples of portable solar chargers, portable battery packs, a combination of the two, and other options. The table below offers a comparison of various battery back-up options and the approximate length of time they may be able to run different appliances.

Source: Total Environment Centre

4. If you are able to buy a home battery to store rooftop solar energy, make sure it can also operate as a backup power supply.

Not all batteries can operate in stand alone mode. And you need to make sure it has enough capacity to power your essential services.

5. If you are thinking of buying an electric vehicle,think about getting one which can power plug-in appliances (“vehicle to load” orV2L).

The report describes V2L – while limited in availability in Australia at the moment, in terms of EV models that offer the function – as “an excellent energy resilience solution,” thanks to its inherent portability (battery on wheels) and storage capacity. (See table above)

“A typical EV battery with a state of charge of only 10% would still have usable energy capacity many times greater than the portable power packs described earlier in the report,” Platt writes.

Source: Total Environment Centre

6. Talk to your neighbours and local council about what community facilities are critical to keep operating during blackouts (eg, evacuation centres, health services, emergency services, general stores, and petrol and EV charging stations), and how this might be achieved.

There are a number of measures communities can put into place to act as a backstop for residents in a prolonged energy outage. Once suggestion Platt makes – albeit in the “not commercially available” section – is the establishment of a “battery library.” This is a system of multiple portable batteries, charged by solar and kept at a centralised emergency response centre. These portable batteries can be taken to local houses or businesses where they may be able to provide 1-2 days of back-up power to critical appliances. Platt says that while this solution is not something that is currently used in Australia, the concept is based on commercially available technology and would be easy enough to set up.

7. Practice what you would do in an emergency, and make sure that your equipment is working safely and is charged or otherwise ready for use at short notice.

This speaks for itself.

—

“People often think [energy resilience] means going totally off the grid, either at great expense or by doing without a lot of normal comforts like air conditioning and space heating,” says TEC’s energy market advocate Mark Byrne.

“However, Dr Platt’s report discusses a range of other options. At the expensive end of the spectrum that might include buying an electric car which can use its battery to power appliances in a blackout.

“But some of the most useful advice is extremely cheap, like buying a wind-up radio which has a small battery that can help to charge your phone. That can keep you in touch with the outside world, which can be a lifesaver when the grid goes down and a bushfire or flood is heading your way,” Byrne says.

“It’s also important to plan long-term and think about reducing your overall energy consumption, where you can do that without compromising your safety or comfort. This makes the prospect of a prolonged outage easier to manage.”

Sophie is editor of One Step Off The Grid and deputy editor of its sister site, Renew Economy. Sophie has been writing about clean energy for more than a decade.